I worked in local broadcasting for the better part of a decade.

My first job out of college was as a Web Producer in the Grand Rapids, Michigan, market. My job was basically to cut up what was on the news broadcasts, post it to the TV station’s website, and share it on social media. I also had to find national news stories that were “of interest”1 and do the same thing.

No matter what was happening in the news, we were always told that weather was one of the main driving forces of viewership. I could see it in the online click rates, too; people simply love hearing about the weather.

Even with the advent of smartphones, and with them the ability to check the weather in real-time, all the time, it remained the main draw of local TV news for the entire time I worked in the industry. As my job evolved with the capabilities and algorithms of social media outlets, one of my primary duties became scheduling and filming a live weather forecast directly on Facebook. This would attract hundreds of people, and the meteorologists could respond to comments in real time.

The continued draw of TV weather is simple: People2 want to be told what is going to happen. Not by their phone, but by someone with polish, authority, and a big map. We can look at the Weather app and see for ourselves that it’s going to rain, but for some reason, it’s more impactful for some of us to have it confirmed by a professional in between scare stories about crime and high school football.

And it’s better if there’s a little showmanship. The weather person must stand in front of a monitor, waving their hands in front of a green screen, showing us the coming storm as it moves across the viewing area.

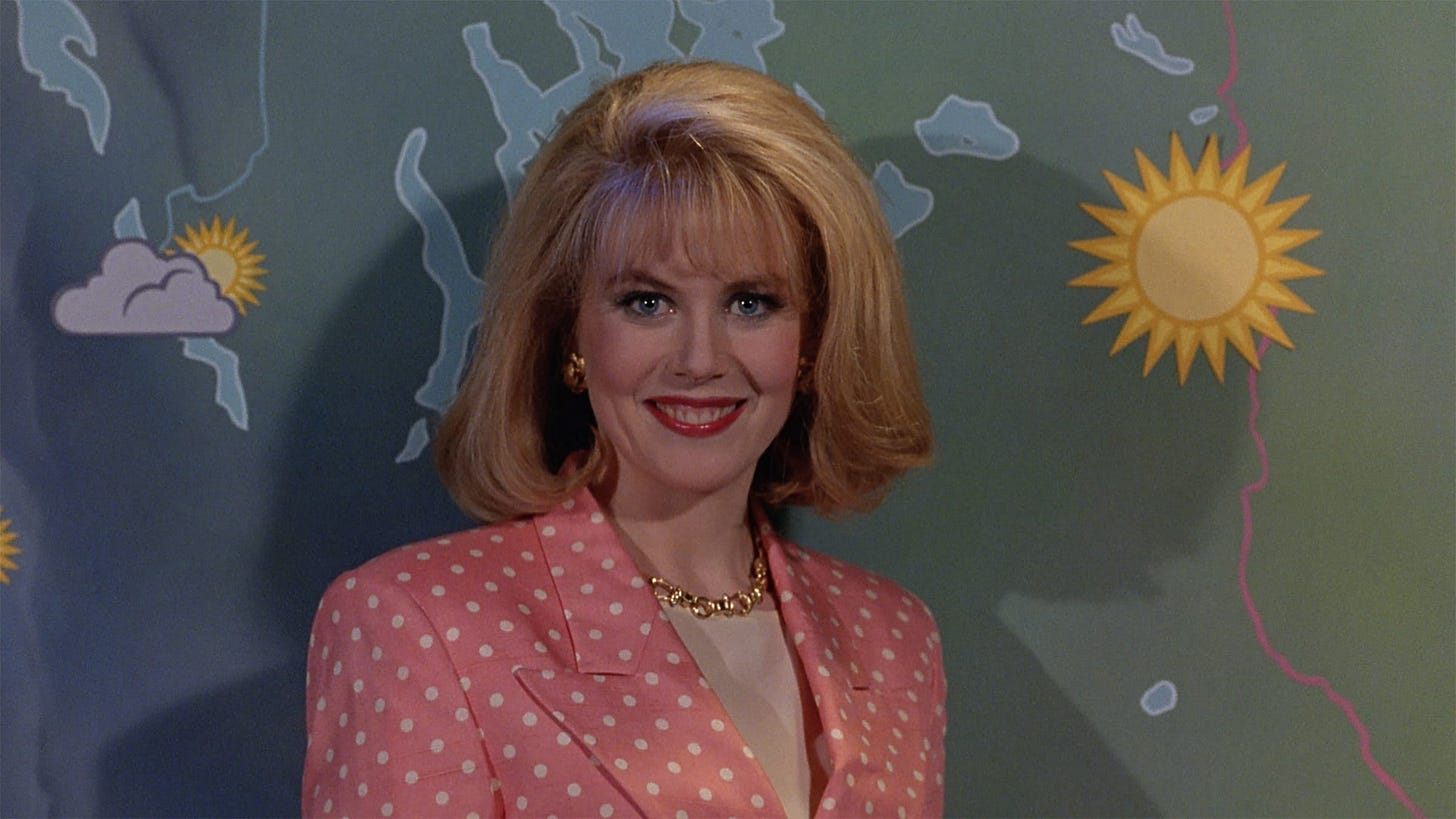

To Die For, Gus Van Sant’s ruthless, propulsive slice of ‘90s neo-noir, does away with nearly everything about the news except the weather. This makes sense in the context of its single-minded antiheroine, aspiring on-air correspondent Suzanne Stone (Nicole Kidman3). Wherever Suzanne goes, she is the eye of the storm; her magnetism draws people into her orbit, and she spits them out (or worse) once they’ve served their purpose.

Suzanne is ambitious to the point of psychopathy, her beaming smirk and collection of gaudy outfits barely papering over a nasty off-camera mean streak. It’s a role that could have easily leaned on stereotypes - of TV news people, of cutthroat career women, of blondes. However, Kidman inhabits the character so fully and without any ironic distance that Suzanne becomes much more than a deranged spectacle.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Normal Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.